The box office king and Trump golf antagonist beat a crack addiction to build a film career unrivaled in modern stardom, and the 70-year-old ‘Glass’ actor aims to work well into his 80s — if Marvel and the rest of Hollywood can afford him: “I’m a gunslinger now.”

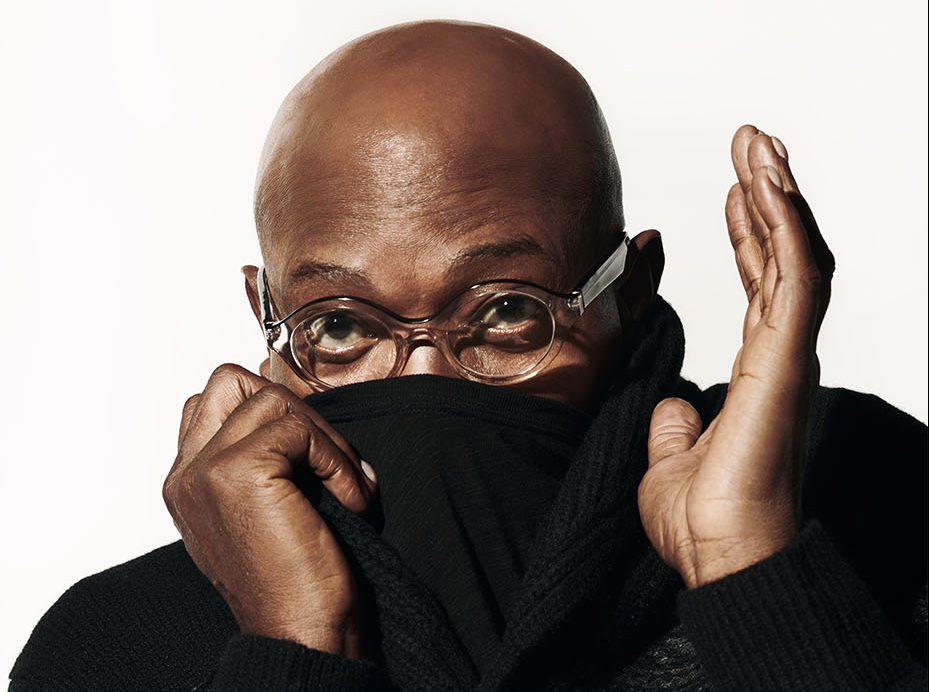

He arrives exactly on schedule, not a minute early, not a minute late, and comes dressed in character: Armani cashmere shirt, translucent Alain Mikli eyeglasses and, of course, a Kangol cap. There are no formalities, no handshakes, no, “Hi, nice to meet you, I’m Samuel L. Jackson.” He simply strolls into the restaurant in midtown Manhattan — a short walk from the $13 million condo he shares with his wife of 38 years, LaTanya Richardson, who’s currently starring as Calpurnia in Aaron Sorkin’s Broadway adaptation of To Kill a Mockingbird — slips into a corner booth and buries his face behind a menu.

“Go ahead,” he says. “I’m listening.”

This is how the world’s most successful actor begins an interview.

That superlative is not a total exaggeration; it’s been scientifically proven. Jackson, who just celebrated his 70th birthday, is “the most influential actor of all time,” according to a study published in December in Applied Network Science that used an algorithm to measure various actors’ impact on pop culture (Clint Eastwood and Tom Cruise came in second and third). In September, Box Office Mojo did its own calculation, naming Jackson Hollywood’s most bankable star. His 120-plus movies — from tentpoles (Jurassic Park and the Star Wars prequels) to art house hits like Pulp Fiction to campy horror neo-classics like Snakes on a Plane — have earned a grand total of $5.76 billion at the U.S. box office (well ahead of Harrison Ford’s $4.96 billion and Tom Hanks’ $4.6 billion), and a staggering $13.3 billion worldwide.

Of course, a big chunk of those billions comes from the Marvel Cinematic Universe (nine of the highest-grossing films of the past decade), in which Jackson plays Avengers boss Nick Fury, a role he took up almost as a lark in 2008 and is about to reprise yet again in Captain Marvel, opening March 8. But just a few months before that, on Jan. 19, he’ll also be starring in another superhero sequel, Glass, M. Night Shyamalan’s follow-up to 2000’s Unbreakable, in which Jackson again plays Elijah Price, also known as Mr. Glass, a brittle-boned, wheelchair-bound genius on the hunt for mutants among us (think Magneto in a Frederick Douglass wig). Even if you don’t count his ubiquitous Capital One commercials — for which he earns eight figures a year — you don’t need an algorithm to compute just how big a first quarter this may be for Jackson, who has averaged about five movies a year for the past three decades.

“That’s his superpower,” says Shyamalan. “He genuinely loves to entertain people. It’s something he finds great pride in.” Of course, being the most famous badass on the silver screen, deliverer of some of cinema’s most beloved obscenity-laden bon mots, has its downside. The shouts of “Hey, call me a motherfucker!” from fans on the street aren’t always a welcome distraction. But Jackson has learned to be cool with it (he couldn’t resist commending freshman Rep. Rashida Tlaib’s recent use of his favorite epithet, tweeting that he wanted to “wholeheartedly endorse your use of & clarity of purpose when declaring your Motherfucking goal” of impeaching President Trump). He’s learned to be cool with everything. “You know how many actors go through their careers and people can’t repeat one fucking line they ever had?” he says after putting down the menu. “I’m a walking T-shirt. It’s better than not being known for anything.”

***

Jackson has become such a pop culture icon that screenplays are not just being written for him — as Quentin Tarantino did with 1994’s Pulp Fiction — but about him: A script called The Kings of Cool landed on this year’s Black List survey of the industry’s best unproduced screenplays. Over lunch, I read him the logline: “During segregation in the 1960s American South, a nerdy teen tries to win a student election at an all-black high school, but he’ll have to defeat a blossoming badass named Samuel L. Jackson to do so.” At first he nods slowly but says nothing. Then I mention the name of the screenwriter: Jon Dorsey. For the first time in our conversation, a broad smile crosses Jackson’s face. “Is that William Dorsey’s son?” he asks (the answer is yes, it is). “That was the guy who ran against me for student body president. But I was the nerdy teen. He was the cool guy. Dorsey was way cooler than I was.” Who won the election? “I did,” Jackson says, still smiling.

One of his earliest memories is of playing a Sugar Plum Fairy in The Nutcracker at age 3. “And I remember some Western-themed pageant where I had bells on my ankles and wrists and a loincloth and long Indian headdress,” he says. “And I remember being Humpty Dumpty falling off a wall.” It was his aunt who first pushed him onto the stage; his mom, a government worker, had left him to be raised by her sister in Tennessee for most of his early childhood. His father wasn’t in the picture; in fact, Jackson met him only twice before he died. The first time he was too young to remember, but the second was when Jackson was in his 30s, while crisscrossing the country in a bus-and-truck theater tour. He had decided to pay a visit with his newborn daughter — Zoe Jackson, now 36 and a supervising producer on Bravo’s Top Chef — to his paternal grandmother while passing through Kansas City. She’d always been sweet to him, sending him birthday and Christmas cards. But Jackson didn’t realize until he arrived at her home that his father was still living with her.

“We talked,” he recalls. “He started telling me about all the other kids he had. ‘You have brothers and sisters here and there.’ I’m going, ‘You know, I’m good being an only child.'”

Growing up in the segregated South and coming of age in the turbulent 1960s, Jackson found himself at the nexus of radical politics. As a student at the all-male, historically black Morehouse College, he’d been an usher at Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral in 1968, but after King’s assassination he began to relate more to non-pacifist activists, like H. Rap Brown and Stokely Carmichael. “It was easier for me to side with their ideology

[than with King’s]

,” he explains, “or understand that ‘violence is as American as cherry pie,’ as Brown put it. That made sense to me, you know? Somebody hits you, you hit them back.”

Jackson’s politics today are more modulated, but he still doesn’t believe in pulling punches. “When I hear ‘Make America Great Again,’ I hear something else. When I see the president and Mitch McConnell and Jeff Sessions going on with that twang, that’s a trip in memory hell. And that does anger me.”

Like everybody else these days, he often expresses that anger on Twitter, where he has 7.7 million followers. In recent months, he’s called the president a “busted condom” and a “hemorrhoid” and once, in 2016, got into a tweet war with the then-candidate, accusing Trump of cheating during a golf game. When Trump responded that he and Jackson had never teed off together, Jackson posted the receipt from their game. “I’ve been reported to Twitter a lot,” he says with a laugh. “Whatever. But sometimes I’ll get a call from my representatives and they’ll go, ‘Can you not tweet for a while?'”

It was also during the 1960s that Jackson began experimenting with drugs, a habit that clung to him for years and nearly destroyed his life. It started when a Merry Prankster-esque professor turned him on to LSD, but Jackson quickly branched out into heroin, cocaine and, by the 1980s, crack. That last one stuck, and for 15 years he maintained a mostly functional addiction, smoking crack the way some people drink Starbucks lattes.

In the early 1990s, Jackson was understudying on Broadway for the lead in August Wilson’s The Piano Lesson. “I had to sit there every night on the steps behind the theater and listen to Charles Dutton do that part,” Jackson says. “I’d sit there and smoke crack while I listened to the play. It made me fucking crazy. Because I’d be listening to him doing the lines and going, ‘That’s not right!'”

One night, Jackson looked down from a perch while puffing on a glass pipe and spotted Jessica Lange below, taking a smoke break while appearing in A Streetcar Named Desire across the street. A few years later, the two were starring together in Losing Isaiah. “We would smoke cigarettes together in the rain under this awning where we were shooting in Chicago,” Jackson recalls. “It was fun. But I never said, ‘Hey Jessica, I used to watch you while smoking crack’ or nothing.”

For Jackson, rock bottom arrived when his wife and daughter discovered him lying face-down and unconscious on the kitchen floor, surrounded by drug paraphernalia. Richardson — who refers to this period as her “villa in hell” — insisted Jackson go to rehab, which he did. He was ready. “I’d been getting high since, shit, 15, 16 years old, and I was tired as fuck,” he says. While detoxing, he was sent a script by Spike Lee, for whom he had already done a string of smaller roles in films like Do the Right Thing and Mo’ Better Blues. Lee wanted him to play Gator, the crackhead brother of Wesley Snipes’ character in the interracial romance Jungle Fever. Ironically, the first role Jackson would take as a sober actor would require him to play a crack addict. “All the people in rehab were trying to talk me out of it,” he recalls. ” ‘You’re going to be messing around with crack pipes. All your triggers will be there. Blah, blah, blah.’ I was like, ‘You know what? If for no other reason than I never want to see you motherfuckers again, I will never pick up another drug.’ ‘Cause I hated their asses.”

Around the time of the movie’s release, Jackson had an inside joke with his agent, Toni Howard of ICM Partners, who has represented him for 25 years. Jackson had watched over a number of years as members of his circle of actor friends — first Morgan Freeman, then Denzel Washington, then Snipes, then Laurence Fishburne — would jet off to Hollywood to make names for themselves. “I’d call my agent and say, ‘Hollywood call?’ And she’d always go, ‘No.'” But when Jungle Fever premiered at Cannes in 1991 — Lee did not fly Jackson to the festival, explaining that there was only budget to bring “the stars” — Jackson’s performance as Gator caused such a sensation that the jury honored it with the festival’s first, and only, best supporting actor award. “That day I’m out at some audition,” Jackson recalls, “and I called my agent, and said, ‘Did Hollywood call?’ And she’s like, ‘As a matter of fact, they kind of did.'” Lee has never apologized to Jackson for leaving his breakout star back in the U.S. “Not only that,” Jackson says, “when he came back, he didn’t actually give me my goddamn award for, like, eight months!”

It didn’t matter. Jackson’s canonization by the international film community changed everything. “That was pretty much the end of me beating the pavement in New York,” he says. A slew of film roles started coming his way: Patriot Games, Amos and Andrew, National Lampoon’s Loaded Weapon. For those early parts, he was never the first choice — “Every script had, shit, Forest Whitaker, Denzel, Larry Fishburne’s fingerprints,” he recalls — but he was thrilled to have a seat at the table. He was also earning big paychecks. “I got to Hollywood at the right time, when the second-fiddle check was better than the leading-man check is now. Hollywood was just throwing money at movies.”

It was in a nondescript office in 1991 that he met the person perhaps most responsible for promulgating his “coolest man on Earth” persona. Quentin Tarantino was a 28-year-old video store clerk who, with money made selling a spec screenplay called Natural Born Killers, was funding and casting his first feature, the bloody crime caper Reservoir Dogs. Jackson had no idea who Tarantino was. He thought he might be an actor, possibly the worst he’d ever read with — second only to Lawrence Bender, the film’s producer, who read the other part at the audition. “They were horrible,” Jackson says. “I was like, ‘Who were those awful motherfuckers?'”

Jackson did not get the part of Holdaway, the cop who teaches Tim Roth’s undercover Mr. Orange the “commode story.” But he was in the Sundance audience when the film premiered the following year. “I was thinking, ‘Well, good movie.’ Then I realized that dude who I read with was the director! So I go over to him and tell him how much I liked the movie but how it would’ve been a better movie with me in it. So he said, ‘Well, I’m writing something right now for you.’ I was like, ‘Really? You remember me that well?’ And then about two weeks later, Pulp Fiction came.”

Jackson read the script twice. “I vividly remember getting to the end of it and being like, ‘Wow. Get the fuck outta here. Is this shit that good or am I just thinking, because he wrote it for me, I think it’s that good?’ So boom, I flipped it over and read it through again.” It was that good.

Jackson and Bruce Willis didn’t have many scenes together, but the two actors forged a friendship that carried over to the set of Die Hard With a Vengeance, in which Jackson played the sidekick role of Zeus Carver. In May 1994, the pair took a break from filming Vengeance to fly to Cannes for the world premiere of Pulp Fiction. Willis wasn’t convinced there would be an audience for it. At one point in the screening, he whispered into Jackson’s ear: “This movie’s OK, but Die Hard‘s going to change your life. This movie’s not going to change your life.”

Willis was half right: Vengeance made Jackson an international star, but the art house crossover Pulp Fiction was heralded as an instant classic. Says Jackson, “It’s the kind of movie that every year, I gain 3, 4 million new fans because kids get old enough to see it for the first time. They think it’s the coolest thing they’ve ever fuckin’ seen in their lives.”

Count Shyamalan among those fans. “It really is just one of my favorite movies,” he says. “Bruce and Sam both had this swagger that I liked.” Coming off his massively successful collaboration with Willis on The Sixth Sense, Shyamalan could have cast anyone he wanted to play the antagonist in Unbreakable, what he calls an “urban, hip comic book movie.” But he wanted Jackson. This was 1999 — a time “when everyone wasn’t talking about comic books,” Shyamalan notes — but to the director’s delight, he learned from an initial phone conversation that Jackson was a lifelong devotee of comics. For years following Unbreakable‘s release, they’d sporadically run into each other — typically driving past each other on a studio lot — and Jackson would shout out, “Yo! When we making that sequel, motherfucker?” It took 18 years — and the surprise success of 2017’s Split, which was itself a sort of stealth sequel to Unbreakable (you learn only in the film’s last moments that the two movies are connected) — for Jackson to get the answer he wanted.

There was no such wait to revisit Marvel’s Nick Fury. Jackson originated the role with a very brief appearance in 2008’s Iron Man, reprised it two years later in Iron Man 2, then went on to play it seven more times in 10 years. But in a way, he’d been cast in the part without his knowledge back in 2002. Comic book writer Mark Millar was working on a Marvel comic called The Ultimates and decided to model the character after his favorite movie star. “He’s the world’s coolest guy and actually a huge comic fan,” says Millar. “I had no idea when we used his likeness he even knew who the Avengers were.”

Jackson knew, all right. He was such a big comic book fan, he had a box of titles set aside for him regularly at his favorite L.A. comic shop. And he was taken aback when he unexpectedly saw his face in the Avengers comic panels. He called his agents, who called Marvel — not yet owned by Disney — which sheepishly apologized and pledged to put him in the movie adaptations, if there ever were any. And that, serendipitously, is how Jackson ended up landing the linchpin role that ties together the most profitable superhero franchise in Hollywood history.

The upcoming Captain Marvel — which is set in 1995 (Fury’s younger look, created with makeup and CGI, is modeled on Jackson’s face from 1998’s The Negotiator, co-starring Kevin Spacey) and stars Brie Larson as the alien hero — marks the end of his nine-picture deal with Marvel, but he has no plans of retiring the character. He’s already wrapped Spider-Man: Far From Home (opening July 5) and would happily play the part into his 80s. “I could be the Alec Guinness of Marvel movies,” he suggests. His quote has certainly gone up since he signed his original deal in 2008 (he was paid $5 million to star in 2017’s Kong: Skull Island, according to sources with knowledge of the deal, on the strength of his international appeal, and more for Glass). From here on, salary negotiations could get a lot more interesting with the famously thrifty company. Says Jackson: “I’m a gunslinger now.”

***

Several hours pass and the power-lunch rush has dwindled to a few late-afternoon lingerers. Jackson looks a bit spent, perhaps having talked more than he’s accustomed to. He sips a cappuccino and stares out at the quiet dining room. Soon he’ll be back at the condo, greeting his wife following her matinee performance. In a few weeks, he’ll kiss her goodbye and jet off to a movie set somewhere on the globe — he spends nine months of every year on one — passing the downtime reading scripts and comic books in his trailer. He de-stresses on the golf course and keeps in shape in a Pilates studio.

His 70th birthday bash was held at Cipriani on 42nd Street, where George Lucas gave a toast and Stevie Wonder sang “Happy Birthday.” The guest list, curated by his wife, included some not-as-famous blasts from Jackson’s past. “Some of them made it, some of them are still going to auditions,” he says. “People always say, ‘Wow, you’ve changed.’ But most of the time, you don’t change, the people around you change. You don’t travel in the same circles anymore.”

The party was fun, but to Jackson, the milestone is just another number. From where he’s at, surveying his life and career, his front-row seat to the best and worst of American history, he’s not pining for anything he doesn’t already have. Awards have thus far eluded him — he’s been nominated once for an Oscar (for Pulp Fiction) and for a handful of Golden Globes, but never closed the deal. Still, that kind of recognition isn’t going to validate him. “I did what I always set out to do,” he says, adjusting his Kangol hat before heading for the exit. “I set out to have a great body of work and enjoy it. And that’s exactly what I did.”

Published by Hollywoodreporter.com